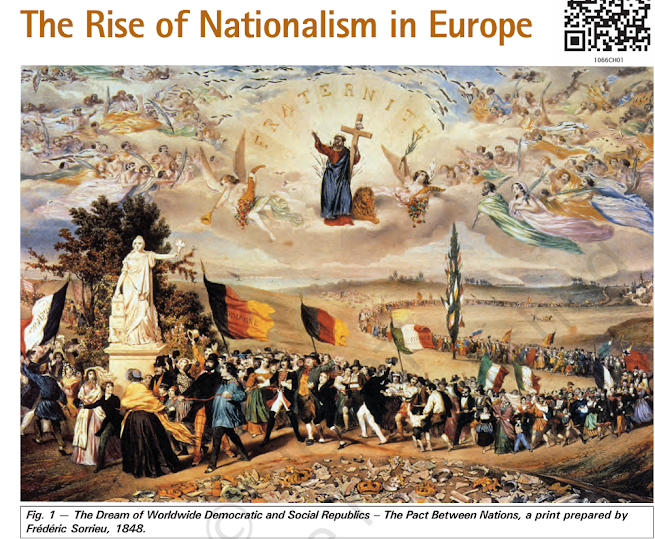

The French Revolution Class 9 History | CBSE Notes, NCERT Solutions & Exam Guide

The French Revolution was a pivotal event in the making of the modern world, fundamentally changing the concepts of liberty, freedom, and equality that are often taken for granted today.

I. Context and Pre-Revolutionary France (The Old Regime)

-

Financial Crisis and Debt

- In 1774, Louis XVI ascended the throne of France, finding an empty treasury.

- This was largely due to long years of war that had drained France's financial resources, including the cost of maintaining an extravagant court at Versailles.

- France's assistance to the thirteen American colonies in gaining independence from Britain further added over a billion livres (French currency, discontinued in 1794) to an existing debt of more than 2 billion livres.

- Lenders began charging 10% interest on loans, forcing the government to spend an increasing percentage of its budget on interest payments alone.

- To cover regular expenses like maintaining the army, court, government offices, or universities, the state was compelled to increase taxes.

-

French Society: The Three Estates

- French society in the 18th century was divided into three estates, a system based on the feudal order of the Middle Ages, known as the Old Regime.

- First Estate: Comprised the Clergy, who enjoyed privileges by birth, including exemption from state taxes. They also extracted taxes called "tithes" from peasants.

- Second Estate: Consisted of the Nobility, also enjoying privileges by birth, notably exemption from state taxes and feudal privileges. These included feudal dues extracted from peasants, who were obliged to provide services like working in the lord's house and fields, serving in the army, or building roads.

- Third Estate: Included everyone else, from big businessmen, merchants, and court officials to lawyers, peasants, artisans, landless laborers, and servants. Crucially, only members of the third estate paid taxes. This estate included both wealthy and poor individuals.

- Peasants made up about 90% of the population, but only a small portion owned the land they cultivated; about 60% of the land was owned by nobles, the Church, and richer members of the third estate.

-

The Struggle to Survive (Subsistence Crisis)

- France's population grew significantly from about 23 million in 1715 to 28 million in 1789.

- This led to a rapid increase in demand for foodgrains, which production could not match.

- The price of bread, the staple diet for most, rose rapidly. Wages, fixed by workshop owners, did not keep pace with prices, widening the gap between rich and poor.

- Droughts or hail further worsened harvests, frequently leading to a subsistence crisis—an extreme situation where basic means of livelihood are endangered.

II. Emergence of New Ideas and the Middle Class

-

Role of the Middle Class

- While peasants and workers had revolted against taxes and food scarcity in the past, they lacked the means and programs for large-scale social and economic change.

- The 18th century saw the emergence of a "middle class" within the Third Estate, who gained wealth through overseas trade and the manufacture of textiles (woollen and silk).

- This group included merchants, manufacturers, lawyers, and administrative officials. They were educated and believed that social position should be based on merit, not birthright.

-

Influential Philosophers

- Ideas for a society based on freedom, equal laws, and opportunities for all were championed by philosophers:

- John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, sought to refute the divine and absolute right of the monarch.

- Jean Jacques Rousseau proposed a government founded on a social contract between the people and their representatives in The Social Contract.

- Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, advocated for a division of power within government among the legislative, executive, and judiciary. This model was implemented in the USA after its independence from Britain, serving as an important example for French political thinkers.

- Ideas for a society based on freedom, equal laws, and opportunities for all were championed by philosophers:

-

Spread of Ideas

- These philosophical ideas were widely discussed in salons and coffee-houses and disseminated through books and newspapers.

- They were often read aloud for the benefit of those who could not read, spreading awareness and generating anger against the system of privileges when news of Louis XVI's planned new taxes emerged.

III. The Outbreak of the Revolution (1789)

-

Convocation of the Estates General

- Under the Old Regime, the monarch could not unilaterally impose taxes; he had to call a meeting of the Estates General. The last meeting before 1789 was in 1614.

- On May 5, 1789, Louis XVI convened the Estates General to pass new tax proposals at Versailles.

- The First and Second Estates sent 300 representatives each, while the Third Estate sent 600, primarily prosperous and educated members. Peasants, artisans, and women were denied entry but their grievances were submitted in 40,000 letters.

-

Voting Dispute and the National Assembly

- Historically, each estate had one vote. Louis XVI insisted on continuing this practice.

- The Third Estate demanded that voting be conducted by the assembly as a whole, with each member having one vote, aligning with Rousseau's democratic principles from The Social Contract.

- When the king rejected this, the Third Estate representatives walked out.

- On June 20, 1789, they assembled at an indoor tennis court in Versailles, declared themselves a National Assembly, and swore not to disperse until they had drafted a constitution limiting the monarch's powers (Tennis Court Oath). They were led by Mirabeau (a noble convinced of abolishing feudal privilege) and Abbé Sieyès (who wrote 'What is the Third Estate?').

-

Storming of the Bastille

- On July 14, 1789, Paris was in alarm as rumors spread that the king ordered troops into the city to fire on citizens.

- About 7,000 men and women formed a peoples' militia, breaking into government buildings for arms.

- A crowd stormed the Bastille fortress-prison, hoping to find ammunition. The commander was killed, and prisoners were released (though only seven). The Bastille symbolized the despotic power of the king and was demolished, with its fragments sold as souvenirs.

- This event is seen by historians as the beginning of a chain of events leading to the king's execution, though unforeseen at the time.

-

Peasant Revolts and Abolition of Feudalism

- Rioting spread to Paris and the countryside, largely driven by protests against high bread prices.

- In the countryside, rumors of brigands hired by lords to destroy crops caused a "Great Fear".

- Peasants attacked chateaux (castles/stately residences), looted hoarded grain, and burned documents recording manorial dues. Many nobles fled.

- Faced with widespread revolt, Louis XVI recognized the National Assembly and accepted that his powers would be checked by a constitution.

- On August 4, 1789, the Assembly passed a decree abolishing the feudal system of obligations and taxes. The clergy were also forced to give up privileges, tithes were abolished, and Church lands were confiscated, netting the government 2 billion livres.

IV. France Becomes a Constitutional Monarchy (1791)

-

The Constitution of 1791

- The National Assembly completed the constitution draft in 1791. Its primary goal was to limit the monarch's powers.

- Powers were separated and assigned to the legislature, executive, and judiciary, making France a constitutional monarchy.

- The National Assembly (745 members) held the power to make laws and was indirectly elected.

-

Voting Rights (Limited Franchise)

- Not all citizens could vote. Only men aged 25 and above who paid taxes equivalent to at least 3 days of a laborer's wage were deemed "active citizens" and entitled to vote (about 4 million out of 28 million population).

- The remaining men, all women, and children were classified as "passive citizens" and had no voting rights.

- To be an elector or an Assembly member, one had to belong to the highest tax bracket.

-

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (DRMC)

- The Constitution began with this Declaration, establishing rights as "natural and inalienable," meaning they belonged to every human by birth and could not be taken away.

- Key rights included:

- Right to life, freedom of speech, freedom of opinion, equality before law.

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.

- Aim of political association: preservation of liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- Sovereignty resides in the nation; no individual/group can exercise authority without popular mandate.

- Liberty is the power to do whatever is not injurious to others.

- Law can only forbid injurious actions; it is the expression of general will, and all citizens (personally or via representatives) have a right to participate in its formation. All citizens are equal before it.

- Freedom of speech, writing, and printing (with responsibility for abuse).

- A common tax is indispensable for public force and administration expenses; it must be assessed equally on all citizens in proportion to their means.

- Property is a sacred and inviolable right; deprivation only for legally established public necessity with just compensation.

- Journalist Jean-Paul Marat criticized this constitution, arguing it gave power to the rich, and that the poor's lot wouldn't improve by peaceful means, anticipating further unrest.

-

Political Symbols

- Symbols were crucial for communicating ideas to a largely illiterate population:

- Snake biting its tail (ring): Symbol of Eternity.

- Sceptre: Symbol of royal power.

- Eye within a triangle radiating light: All-seeing eye (knowledge), rays drive away ignorance.

- Bundle of rods (fasces): Strength in unity.

- Broken chain: Freedom from fetters/slavery.

- Red Phrygian cap: Cap worn by a slave becoming free (symbol of liberty).

- Blue-white-red: National colors of France.

- Winged woman: Personification of the Law.

- Law Tablet: Law is the same for all, and all are equal before it.

- Symbols were crucial for communicating ideas to a largely illiterate population:

V. France Abolishes Monarchy and Becomes a Republic (1792)

-

War and Continued Tensions

- Despite Louis XVI signing the Constitution, he secretly negotiated with the King of Prussia.

- Neighboring rulers were worried and planned to send troops.

- In April 1792, the National Assembly declared war against Prussia and Austria, seen as a war of the people against European kings and aristocracies.

- The Marseillaise, composed by Roget de L'Isle, became a patriotic song and later the national anthem of France.

- These wars brought economic difficulties, with women largely left to support families as men fought.

-

Rise of Political Clubs (Jacobins)

- Many believed the revolution needed to go further, as the 1791 Constitution only benefited the richer sections.

- Political clubs became important for discussing government policies and planning action. The most successful was the Jacobin club, named after a former convent.

- Jacobins primarily comprised less prosperous sections: small shopkeepers, artisans (shoemakers, pastry cooks, watch-makers, printers), servants, and daily-wage workers.

- Their leader was Maximilian Robespierre.

- Jacobins wore long striped trousers (unlike nobles' knee breeches) to distinguish themselves, earning them the name "sans-culottes" (literally "those without knee breeches"). Sans-culottes men also wore the red cap of liberty, though women were not allowed to.

-

Insurrection of August 1792

- In summer 1792, angered by food shortages and high prices, the Jacobins planned an insurrection.

- On August 10, they stormed the Palace of the Tuileries, massacred the king's guards, and held the king hostage.

- The Assembly voted to imprison the royal family.

-

Abolition of Monarchy and Republic Declaration

- Elections were held, and all men aged 21 and above, regardless of wealth, gained the right to vote.

- The newly elected assembly was called the Convention.

- On September 21, 1792, the Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. A republic is a government where people elect the head of government, without hereditary monarchy.

- Louis XVI was sentenced to death for treason and publicly executed on January 21, 1793, at the Place de la Concorde. Queen Marie Antoinette met the same fate shortly after.

VI. The Reign of Terror (1793-1794)

-

Robespierre's Policies

- This period was characterized by severe control and punishment under Robespierre's leadership.

- "Enemies" of the republic—ex-nobles, clergy, members of other political parties, and even dissenting members of his own party—were arrested, imprisoned, and tried by a revolutionary tribunal.

- Those found "guilty" were guillotined, a device designed for beheading, named after Dr. Guillotin.

-

Social and Economic Reforms (and Restrictions)

- The government issued laws imposing maximum ceilings on wages and prices.

- Meat and bread were rationed.

- Peasants were forced to transport grain to cities and sell it at government-fixed prices.

- The use of expensive white flour was forbidden; all citizens were required to eat pain d’égalité (equality bread), made of wholewheat.

- Equality was also promoted through forms of speech: traditional "Monsieur" and "Madame" were replaced with "Citoyen" (Citizen) and "Citoyenne" (Citizen) for all French men and women.

- Churches were shut down and converted into barracks or offices.

-

End of the Reign of Terror

- Robespierre's relentless pursuit of these policies led even his supporters to demand moderation.

- He was convicted by a court in July 1794, arrested, and guillotined the next day.

VII. A Directory Rules France (Post-Terror)

-

Wealthier Middle Class in Power

- The fall of the Jacobin government allowed the wealthier middle classes to seize power.

- A new constitution was introduced that denied voting rights to non-propertied sections of society.

- It established two elected legislative councils which then appointed a Directory, an executive body of five members.

- This structure aimed to prevent the concentration of power in one man, as seen under the Jacobins.

- However, Directors often clashed with legislative councils, leading to political instability.

-

Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte

- This political instability ultimately paved the way for the rise of a military dictator, Napoleon Bonaparte.

- In 1804, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of France.

- He conquered neighboring European countries, replacing dynasties with his family members.

- Napoleon saw himself as a modernizer, introducing laws for protection of private property and a uniform system of weights and measures (decimal system).

- Initially seen as a liberator, his armies were soon viewed as an invading force.

- Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815.

- Despite his rule, many of his measures carried the revolutionary ideals of liberty and modern laws to other parts of Europe, impacting people long after his defeat.

VIII. Women and the Revolution

-

Women's Active Participation

- Women were active participants from the beginning, hoping their involvement would pressure the government to improve their lives.

- Most women of the Third Estate worked for a living as seamstresses, laundresses, vendors, or domestic servants, but had limited access to education or job training. Only daughters of nobles or wealthy Third Estate members could study in convents.

- Working women also had domestic responsibilities and faced lower wages than men.

-

Women's Political Clubs and Demands

- To discuss their interests, women formed their own political clubs and newspapers; about sixty such clubs emerged in French cities.

- The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women was the most famous.

- Their main demand was for equal political rights as men, including the right to vote, to be elected to the Assembly, and to hold political office, believing this was essential for their interests to be represented. They were disappointed by the 1791 Constitution reducing them to passive citizens.

-

Revolutionary Government's Measures for Women

- In the early years, the revolutionary government introduced laws to improve women's lives:

- State schools were created, and schooling became compulsory for all girls.

- Fathers could no longer force daughters into marriage.

- Marriage became a free contract registered under civil law.

- Divorce was legalized and could be applied for by both men and women.

- Women could now train for jobs, become artists, or run small businesses.

- In the early years, the revolutionary government introduced laws to improve women's lives:

-

Suppression and Continued Struggle

- During the Reign of Terror, the government ordered the closure of women's clubs and banned their political activities. Many prominent women were arrested and executed.

- The struggle for voting rights and equal wages continued for two centuries globally, notably through the international suffrage movement.

- French women finally won the right to vote in 1946.

-

Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793)

- A significant politically active woman, she protested the exclusion of women from the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen.

- In 1791, she wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizen, addressing it to the Queen and National Assembly, demanding action.

- She criticized the Jacobin government for closing women's clubs and was tried by the National Convention, charged with treason, and executed in 1793.

- Her Declaration outlined basic rights for women, emphasizing equality with men in rights, sovereignty residing in the union of woman and man, and equal entitlement to public honors and employment based on abilities.

IX. The Abolition of Slavery

-

The Triangular Slave Trade

- Slavery was a key social reform of the Jacobin regime.

- French colonies in the Caribbean (Martinique, Guadeloupe, San Domingo) were crucial suppliers of commodities like tobacco, indigo, sugar, and coffee.

- Due to European reluctance to work in distant lands, a labor shortage on plantations led to a triangular slave trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas, beginning in the 17th century.

- French merchants from ports like Bordeaux and Nantes bought enslaved people from African chieftains, transported them across the Atlantic to the Caribbean, and sold them to plantation owners.

- This exploitation fueled the economic prosperity of French port cities.

-

Debate and Abolition

- Throughout the 18th century, there was little criticism of slavery in France. The National Assembly debated extending "rights of man" to colonial subjects but hesitated to pass laws due to opposition from businessmen dependent on the slave trade.

- The Convention finally legislated to free all enslaved people in French overseas possessions in 1794.

- This was a short-term measure; Napoleon reintroduced slavery ten years later. Plantation owners viewed their freedom as including the right to enslave African people.

- Slavery was finally abolished in French colonies in 1848.

X. The Revolution and Everyday Life

-

Abolition of Censorship

- The years following 1789 saw profound changes in people's lives.

- One significant change was the abolition of censorship soon after the storming of the Bastille.

- Under the Old Regime, all written material (books, newspapers) and cultural activities (plays) required approval from the king's censors.

- The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen proclaimed freedom of speech and expression as a natural right.

-

Spread of Ideas and Public Engagement

- Newspapers, pamphlets, books, and printed pictures flooded French towns and spread rapidly into the countryside, discussing the ongoing changes.

- Freedom of the press allowed for the expression of opposing views, with each side using print to persuade others.

- Plays, songs, and festive processions attracted large audiences, enabling people to grasp and identify with abstract ideas like liberty and justice, which were previously confined to philosophical texts read by a few educated individuals.

XI. Legacy of the French Revolution

-

Ideas of Liberty and Democratic Rights

- The most important legacy was the spread of ideas of liberty and democratic rights from France to the rest of Europe during the 19th century.

- This led to the abolition of feudal systems in many European countries.

-

Impact on Anti-Colonial Movements

- Colonized peoples reinterpreted the idea of freedom from bondage and incorporated it into their movements to establish sovereign nation-states.

- Examples include Tipu Sultan and Rammohan Roy in India, who were inspired by revolutionary France.

- The anti-colonial movements in India, China, Africa, and South America developed innovative ideas but used a language of politics that gained currency from the late 18th century, influenced by the notions of equality and freedom emerging from the French Revolution.

The history of the modern world, as seen through these events, is not just about freedom and democracy, but also about violence, tyranny, death, and destruction.The French Revolution, along with the Russian Revolution and the rise of Nazism, played a crucial role in shaping the modern world. It was instrumental in establishing the concepts of liberty, freedom, and equality, which are often taken for granted today.

Here are the important aspects of the French Revolution, presented in detail:

I. French Society During the Late Eighteenth Century (The Old Regime)

-

Financial Crisis and Debt

- In 1774, Louis XVI ascended the throne and inherited an empty treasury.

- Years of warfare had drained France's financial resources, and the cost of maintaining an extravagant court at the Palace of Versailles further strained finances.

- France's support for the thirteen American colonies in their war for independence against Britain added over a billion livres to an already substantial debt of more than 2 billion livres. (A "livre" was the unit of currency in France, discontinued in 1794).

- Lenders began charging 10 percent interest on loans, forcing the government to dedicate an increasing portion of its budget to interest payments.

- To meet regular expenses, such as maintaining the army, court, government offices, or universities, the state had to increase taxes.

-

The Society of Estates (The Old Regime)

- French society was divided into three estates, a system rooted in the feudal system of the Middle Ages. The term "Old Regime" describes French society and institutions before 1789.

- First Estate: Composed of the Clergy (persons with special functions in the church). They enjoyed privileges by birth, most notably exemption from paying taxes to the state. The Church also extracted taxes called tithes (one-tenth of agricultural produce) from peasants.

- Second Estate: Comprised the Nobility. Like the clergy, they enjoyed privileges by birth, including exemption from state taxes. Nobles also held feudal privileges, extracting feudal dues from peasants. Peasants were obligated to provide services to their lords, such as working in their houses and fields, serving in the army, or building roads.

- Third Estate: This vast group included big businessmen, merchants, court officials, lawyers, peasants, artisans, small peasants, landless laborers, and servants. Crucially, only members of the third estate were burdened with financing state activities through taxes. They paid a direct tax called taille and indirect taxes on everyday items like salt or tobacco. Although primarily poor, some members of the Third Estate were wealthy.

- Peasants constituted about 90 percent of the population, but only a small number owned the land they cultivated. Approximately 60 percent of the land was owned by nobles, the Church, and richer members of the third estate.

-

The Struggle to Survive (Subsistence Crisis)

- France's population grew from around 23 million in 1715 to 28 million in 1789.

- This led to a rapid increase in demand for foodgrains, but production could not keep pace.

- The price of bread, the staple diet for the majority, rose sharply.

- Wages for workers, fixed by employers, did not increase proportionally with prices, leading to a widening gap between the rich and the poor.

- Conditions worsened during droughts or hail, which reduced harvests, frequently causing a subsistence crisis—an extreme situation where basic means of livelihood are endangered.

II. A Growing Middle Class Envisages an End to Privileges

-

Emergence of the Middle Class

- While peasants and workers had revolted against taxes and food scarcity in the past, they lacked the means and plans to enact fundamental changes to the social and economic order.

- The 18th century saw the rise of new social groups, referred to as the middle class, who accumulated wealth through expanding overseas trade and the manufacture of goods like woolen and silk textiles.

- This group included merchants, manufacturers, as well as professionals like lawyers and administrative officials.

- These educated individuals believed that no group in society should be privileged by birth; instead, a person's social position should be based on merit.

-

Influence of Philosophers

- The ideas of a society founded on freedom, equal laws, and equal opportunities for all were championed by prominent philosophers:

- John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, sought to challenge the doctrine of the divine and absolute right of the monarch.

- Jean Jacques Rousseau advanced the concept of a government based on a social contract between people and their representatives in his book The Social Contract.

- Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, proposed a division of power within the government into the legislative, executive, and judiciary. This model was implemented in the USA after its independence from Britain, serving as a significant example for French political thinkers.

- The ideas of a society founded on freedom, equal laws, and equal opportunities for all were championed by prominent philosophers:

-

Dissemination of Ideas

- These philosophical ideas were intensely discussed in salons and coffee-houses and spread through books and newspapers.

- They were often read aloud in groups, making them accessible to those who could not read.

- News of Louis XVI's plan to impose further taxes to cover state expenses sparked widespread anger and protest against the system of privileges.

III. The Outbreak of the Revolution (1789)

-

Convocation of the Estates General

- In the Old Regime, the monarch alone could not impose taxes; he had to call a meeting of the Estates General. The last such meeting before 1789 was in 1614.

- On May 5, 1789, Louis XVI called an assembly of the Estates General to approve new taxes.

- The First and Second Estates sent 300 representatives each, seated in rows, while the 600 members of the Third Estate had to stand at the back. The Third Estate was represented by its more prosperous and educated members, while peasants, artisans, and women were denied entry but their grievances were listed in 40,000 letters.

-

The Tennis Court Oath and the National Assembly

- Historically, voting in the Estates General was by estate, with each estate having one vote. Louis XVI intended to continue this practice.

- However, members of the Third Estate demanded that voting be conducted by the assembly as a whole, with each member having one vote, a democratic principle advocated by Rousseau.

- When the king rejected this proposal, the Third Estate representatives walked out in protest.

- On June 20, 1789, they assembled in the hall of an indoor tennis court in Versailles, declared themselves a National Assembly, and swore not to disperse until they had drafted a constitution to limit the monarch's powers. This event is known as the Tennis Court Oath.

- They were led by Mirabeau (a noble who advocated for ending feudal privilege) and Abbé Sieyès (a priest who wrote the influential pamphlet 'What is the Third Estate?').

-

The Storming of the Bastille

- On July 14, 1789, the city of Paris was in a state of alarm due to rumors that the king had ordered troops to open fire on citizens.

- Around 7,000 men and women gathered, formed a people's militia, and sought arms by breaking into government buildings.

- A large group marched to the eastern part of the city and stormed the Bastille fortress-prison, hoping to find ammunition.

- In the ensuing fight, the Bastille commander was killed, and the seven prisoners were released. The Bastille was hated as it symbolized the despotic power of the king. It was demolished, and its stone fragments were sold as souvenirs.

- Historians view this event as the beginning of a series of events that led to the king's execution, though this outcome was not anticipated at the time.

-

Peasant Revolts and Abolition of Feudalism

- Following the Bastille's fall, more rioting occurred in Paris and the countryside, primarily protesting the high price of bread.

- Rumors spread in the countryside that lords had hired brigands to destroy crops, causing a "Great Fear".

- Terrified peasants in several districts attacked chateaux (castles or stately residences of nobles or kings), looted hoarded grain, and burned documents recording manorial dues. Many nobles fled their homes, some migrating to other countries.

- Facing the power of his revolting subjects, Louis XVI finally recognized the National Assembly and accepted that his powers would henceforth be limited by a constitution.

- On the night of August 4, 1789, the Assembly passed a decree abolishing the feudal system of obligations and taxes.

- Members of the clergy were also compelled to surrender their privileges, tithes were abolished, and Church lands were confiscated, resulting in the government acquiring assets worth at least 2 billion livres.

IV. France Becomes a Constitutional Monarchy (1791)

-

The Constitution of 1791

- The National Assembly completed the constitution's draft in 1791.

- Its primary goal was to limit the monarch's powers.

- These powers, instead of being concentrated in one person, were separated and assigned to different institutions: the legislature, executive, and judiciary, thereby making France a constitutional monarchy.

- The National Assembly (745 members) held the power to make laws and was indirectly elected.

-

Voting Rights (Limited Franchise)

- Not all citizens were granted the right to vote. Only men aged 25 years and above who paid taxes equivalent to at least 3 days of a laborer’s wage were given the status of "active citizens" (approximately 4 million out of a population of 28 million).

- All other men, and all women, were categorized as "passive citizens" and had no voting rights.

- To qualify as an elector or a member of the Assembly, a man had to belong to the highest tax bracket.

-

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (DRMC)

- The Constitution began with this Declaration, proclaiming rights such as the right to life, freedom of speech, freedom of opinion, and equality before law.

- These were established as "natural and inalienable" rights, meaning they belonged to every human being by birth and could not be taken away.

- It was deemed the state's duty to protect these natural rights.

- Key articles included:

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.

- The purpose of political association is to preserve the natural and inalienable rights of man: liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- All sovereignty resides in the nation.

- Liberty means the power to do whatever is not harmful to others.

- Law is the expression of the general will, and all citizens have the right to participate in its formation, either personally or through representatives. All citizens are equal before it.

- Freedom to speak, write, and print freely.

- A common tax is necessary for public force and administration, and it must be assessed equally on all citizens in proportion to their means.

- Property is a sacred and inviolable right; it can only be taken for a legally established public necessity with prior just compensation.

- The revolutionary journalist Jean-Paul Marat criticized this constitution for favoring the rich, stating that the poor and oppressed would not improve their situation through peaceful means alone.

-

Political Symbols

- Given that most men and women in the 18th century could not read or write, images and symbols were extensively used to convey important ideas. Examples include:

- Snake biting its tail to form a ring: Symbol of Eternity.

- Sceptre: Symbol of royal power.

- The eye within a triangle radiating light: The all-seeing eye represents knowledge, with the sun's rays dispelling ignorance.

- The bundle of rods or fasces: Symbolizes strength in unity (one rod is easily broken, but not a bundle).

- The broken chain: Chains were used to shackle enslaved people; a broken chain represents freedom.

- Red Phrygian cap: A cap worn by an enslaved person upon gaining freedom.

- Blue-white-red: The national colors of France.

- The winged woman: Personification of the law.

- The Law Tablet: Signifies that the law is the same for all, and all are equal before it.

- Given that most men and women in the 18th century could not read or write, images and symbols were extensively used to convey important ideas. Examples include:

V. France Abolishes Monarchy and Becomes a Republic (1792)

-

War with Prussia and Austria

- The situation in France remained tense. Louis XVI, despite signing the Constitution, engaged in secret negotiations with the King of Prussia.

- Other neighboring countries' rulers were concerned about developments in France and planned to send troops.

- Before they could act, the National Assembly voted in April 1792 to declare war against Prussia and Austria.

- Thousands of volunteers joined the army, viewing it as a war against kings and aristocracies across Europe.

- The Marseillaise, a patriotic song composed by Roget de L’Isle, was sung by volunteers from Marseilles as they marched into Paris and later became the national anthem of France.

-

Economic Hardship and Political Clubs

- The revolutionary wars brought economic difficulties and losses. Women bore the burden of earning a living and caring for families while men were away fighting.

- Large parts of the population felt the revolution needed to progress further, as the 1791 Constitution only granted political rights to the wealthier sections of society.

- Political clubs became important gathering points for people to discuss government policies and plan actions.

-

The Jacobin Club

- The most successful political club was that of the Jacobins, named after the former convent of St Jacob in Paris.

- Women also formed their own clubs during this period.

- Jacobin members were primarily from the less prosperous sections of society, including small shopkeepers, artisans (shoemakers, pastry cooks, watch-makers, printers), servants, and daily-wage workers.

- Their leader was Maximilian Robespierre.

- A significant group among the Jacobins adopted long striped trousers (similar to dock workers) to distinguish themselves from nobles who wore knee breeches, symbolizing the end of the nobles' power. They became known as the sans-culottes (literally "those without knee breeches"). Sans-culottes men also wore the red cap of liberty, but women were not permitted to.

-

Insurrection and the Abolition of Monarchy

- In the summer of 1792, the Jacobins planned an insurrection due to short supplies and high food prices.

- On August 10, they stormed the Palace of the Tuileries, massacred the king's guards, and held the king hostage for several hours.

- The Assembly subsequently voted to imprison the royal family.

- Elections were held, and for the first time, all men aged 21 and above, regardless of wealth, received the right to vote.

- The newly elected assembly was called the Convention.

- On September 21, 1792, the Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. A republic is a form of government where the people elect their government, including the head of state, and there is no hereditary monarchy.

- Louis XVI was sentenced to death by a court on charges of treason and publicly executed on January 21, 1793, at the Place de la Concorde. Queen Marie Antoinette was executed shortly after.

VI. The Reign of Terror (1793-1794)

-

Robespierre's Strict Policies

- The period from 1793 to 1794 is known as the Reign of Terror.

- Robespierre implemented a policy of severe control and punishment.

- Anyone he deemed an "enemy" of the republic—including ex-nobles, clergy, members of other political parties, and even members of his own party who disagreed with him—were arrested, imprisoned, and tried by a revolutionary tribunal.

- If found "guilty," they were guillotined, a device with two poles and a blade for beheading, named after Dr. Guillotin.

-

Economic and Social Measures

- Robespierre's government imposed laws establishing maximum ceilings on wages and prices.

- Meat and bread were rationed.

- Peasants were forced to transport their grain to cities and sell it at government-fixed prices.

- The use of more expensive white flour was forbidden; all citizens were required to eat pain d'égalité (equality bread), a loaf made of wholewheat.

- Equality was also promoted through forms of address: traditional "Monsieur" (Sir) and "Madame" (Madam) were replaced by "Citoyen" (Citizen) and "Citoyenne" (Citizen) for all French men and women.

- Churches were shut down, and their buildings converted into barracks or offices.

-

Fall of Robespierre

- Robespierre's relentless and severe policies eventually led even his supporters to demand moderation.

- In July 1794, he was convicted by a court, arrested, and guillotined the next day.

VII. A Directory Rules France

-

Shift in Power

- The fall of the Jacobin government allowed the wealthier middle classes to seize power.

- A new constitution was introduced that denied the right to vote to non-propertied sections of society.

- It established two elected legislative councils, which then appointed a Directory, an executive body composed of five members.

- This system was intended to safeguard against the concentration of power in a one-man executive, as had occurred under the Jacobins.

- However, the Directors frequently clashed with the legislative councils, leading to requests for their dismissal.

-

Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte

- The political instability of the Directory created an opening for the rise of a military dictator, Napoleon Bonaparte.

- In 1804, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of France.

- He embarked on conquering neighboring European countries, overthrowing dynasties, and establishing kingdoms for his family members.

- Napoleon viewed himself as a modernizer of Europe, introducing laws such as the protection of private property and a uniform system of weights and measures based on the decimal system.

- Initially, many saw Napoleon as a liberator bringing freedom, but his armies soon became perceived as an invading force.

- He was finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815.

- Despite his defeat, many of his measures, which spread revolutionary ideas of liberty and modern laws across Europe, had a lasting impact.

VIII. Did Women Have a Revolution?

-

Women's Active Participation and Demands

- From the very beginning, women were active participants in the revolutionary events, hoping their involvement would lead the government to improve their lives.

- Most women from the Third Estate worked as seamstresses, laundresses, vendors of flowers/fruits/vegetables, or domestic servants.

- They generally lacked access to education or job training; only daughters of nobles or wealthier Third Estate members could study in convents. Working women also bore the burden of household chores and child-rearing, and their wages were lower than men's.

- To voice their interests, women formed their own political clubs and newspapers; about sixty such clubs emerged in various French cities, with The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women being the most famous.

- Their primary demand was for equal political rights as men, including the right to vote, to be elected to the Assembly, and to hold political office, believing this was essential for their interests to be represented. They were disappointed that the 1791 Constitution reduced them to passive citizens.

-

Revolutionary Government's Measures for Women

- In the early years, the revolutionary government did introduce laws aimed at improving women's lives:

- State schools were created, and schooling became compulsory for all girls.

- Fathers could no longer force their daughters into marriage against their will.

- Marriage was made a civil contract, freely entered into and registered.

- Divorce was legalized, applicable by both women and men.

- Women gained opportunities to train for jobs, become artists, or run small businesses.

- In the early years, the revolutionary government did introduce laws aimed at improving women's lives:

-

Suppression and Continued Struggle

- During the Reign of Terror, the new government issued laws ordering the closure of women's clubs and banning their political activities. Many prominent women were arrested and executed.

- Women's movements for voting rights and equal wages continued for the next two hundred years in many countries, driven by an international suffrage movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- The example of French women's political activities during the revolution served as an inspiring memory.

- Women in France finally won the right to vote in 1946.

-

Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793)

- She was one of the most important politically active women in revolutionary France.

- She protested against the Constitution and the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen for excluding women from basic human rights.

- In 1791, she wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizen, addressing it to the Queen and National Assembly, demanding action.

- In 1793, she criticized the Jacobin government for forcibly closing women's clubs. She was tried by the National Convention, charged with treason, and subsequently executed.

- Her Declaration outlined key rights for women, including being born free and remaining equal to men in rights, the goal of political associations preserving natural rights for both women and men, sovereignty residing in the nation as the union of woman and man, and equal access to honors and public employment based on talents.

IX. The Abolition of Slavery

-

The Triangular Slave Trade

- The abolition of slavery in French colonies was a significant social reform during the Jacobin regime.

- French colonies in the Caribbean (Martinique, Guadeloupe, and San Domingo) were vital suppliers of commodities like tobacco, indigo, sugar, and coffee.

- A shortage of labor on plantations, due to Europeans' reluctance to work in distant lands, led to the triangular slave trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas, which began in the 17th century.

- French merchants sailed from ports like Bordeaux and Nantes to the African coast, where they purchased enslaved people from local chieftains. These individuals were then branded, shackled, and tightly packed onto ships for a three-month voyage across the Atlantic to the Caribbean, where they were sold to plantation owners.

- The exploitation of enslaved labor enabled France to meet the growing European demand for sugar, coffee, and indigo. Port cities like Bordeaux and Nantes prospered economically due to this flourishing slave trade.

-

Legislative Efforts and Reintroduction

- Throughout the 18th century, there was limited criticism of slavery in France. The National Assembly debated extending the rights of man to all French subjects, including those in the colonies, but feared opposition from businessmen whose incomes depended on the slave trade.

- Finally, the Convention, in 1794, legislated to free all enslaved people in French overseas possessions.

- However, this was a short-term measure: Napoleon reintroduced slavery ten years later. Plantation owners viewed their freedom as including the right to enslave African people for their economic interests.

- Slavery was finally abolished in French colonies in 1848.

X. The Revolution and Everyday Life

-

Abolition of Censorship

- The years following 1789 saw numerous changes in the daily lives of men, women, and children in France. Revolutionary governments actively passed laws to translate ideals of liberty and equality into practice.

- An important law enacted soon after the storming of the Bastille was the abolition of censorship.

- Under the Old Regime, all written materials and cultural activities (books, newspapers, plays) required approval from the king's censors before publication or performance.

- The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen proclaimed freedom of speech and expression as a natural right.

-

Spread of Ideas and Public Sphere

- Newspapers, pamphlets, books, and printed pictures proliferated in French towns and quickly spread into the countryside, describing and discussing the ongoing events and changes.

- Freedom of the press also meant that opposing views could be expressed, with each side attempting to convince others through print.

- Plays, songs, and festive processions attracted large numbers of people, providing a way for them to grasp and identify with complex political ideas like liberty or justice, which were previously discussed in texts only accessible to a handful of educated people.

XI. Legacy of the French Revolution

-

Spread of Ideals

- The most significant legacy of the French Revolution was the spread of the ideas of liberty and democratic rights from France to the rest of Europe during the 19th century.

- This influence led to the abolition of feudal systems in many European countries.

-

Inspiration for Anti-Colonial Movements

- The idea of freedom from bondage was reinterpreted by colonized peoples and incorporated into their movements to create sovereign nation-states.

- Individuals like Tipu Sultan and Rammohan Roy in India were inspired by the ideas emerging from revolutionary France.

- Anti-colonial movements in India, China, Africa, and South America developed innovative and original ideas, but they spoke in a political language that gained widespread acceptance only from the late 18th century, profoundly influenced by the concepts of equality and freedom from the French Revolution.

The sources highlight that while the history of the modern world reflects the unfolding of freedom and democracy, it also encompasses violence, tyranny, death, and destruction.

Comments

Post a Comment