Rise of Nationalism in Europe – Class 10 CBSE Detailed Notes | Chapter 1 History

Rise Of Nationalism In Europe of Class 10

Introduction

This chapter tries to explain the meaning of nationalism and how nationalism evolved in mankind’s history. Starting with French Revolution the nationalism spread to other parts of Europe and later on paved the way for development of modern democratic nations across the world.

Credit: NCERT GRADE X CBSE TEXT BOOK

|

Subject |

Social Science (History) |

|

Class |

10 |

|

Board |

CBSE |

|

Chapter

No. |

1 |

|

Chapter

Name |

The Rise of Nationalism in Europe |

|

Type |

Notes |

|

Session |

2025-26 |

|

Weightage |

6 marks |

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Frederic Sorrieu’s Painting

- The French Revolution and the Idea of the Nation

- The Making of Nationalism in Europe

- The Age of Revolutions: 1830-1848

- The Making of Germany and Italy

- Visualising the Nation

- Nationalism and Imperialism

Here are the important pointers from the provided sources, detailed with headings, subheadings, and examples for clarity:

1. The Concept of the Nation-State and Nationalism

-

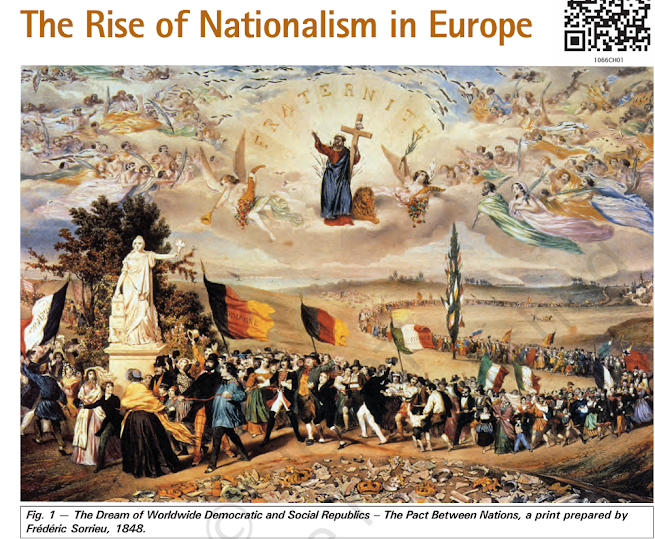

Frédéric Sorrieu's Utopian Vision (1848)

- French artist Frédéric Sorrieu created a series of four prints depicting his dream of a world composed of 'democratic and social Republics'.

- The first print shows people of Europe and America, from all ages and social classes, marching in a procession and paying homage to the Statue of Liberty.

- The Statue of Liberty is personified as a female figure holding the torch of Enlightenment in one hand and the Charter of the Rights of Man in the other.

- In the foreground, shattered remains of symbols of absolutist institutions lie on the ground.

- Sorrieu's vision depicted peoples grouped as distinct nations, identifiable by their flags and national costumes.

- Leading the procession were the United States and Switzerland, which were already nation-states.

- France followed, identifiable by its revolutionary tricolour flag, having just reached the statue.

- The peoples of Germany followed, bearing a black, red, and gold flag, which, at the time, represented liberal hopes for a unified German nation-state under a democratic constitution.

- Other nations in the procession included Austria, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Lombardy, Poland, England, Ireland, Hungary, and Russia.

- Christ, saints, and angels observed from the heavens, symbolizing fraternity among nations.

- Sorrieu's vision is considered utopian, meaning an ideal society unlikely to exist.

-

Defining a Nation and Nation-State

- Nationalism emerged in the nineteenth century as a force that brought significant changes in Europe's political and mental landscape.

- The result was the emergence of the nation-state, replacing multi-national dynastic empires.

- A modern state is characterized by a centralized power exercising sovereign control over a defined territory.

- A nation-state is one where the majority of its citizens, not just rulers, develop a sense of common identity and shared history or descent.

- This commonness was not inherent but forged through struggles and the actions of leaders and common people.

-

Ernst Renan's Understanding of a Nation

- In an 1882 lecture, French philosopher Ernst Renan criticized the idea that a nation is formed by a common language, race, religion, or territory.

- Attributes of a Nation (according to Renan):

- A culmination of a long past of endeavours, sacrifice, and devotion.

- Based on a "social capital" of a heroic past, great men, and glory.

- Essential conditions include common glories in the past, a common will in the present, having performed great deeds together, and the desire to perform still more.

- Defined as a large-scale solidarity.

- Its existence is a "daily plebiscite," meaning a daily affirmation of its inhabitants' will.

- Renan stated that a nation has no real interest in annexing or holding a country against its will, emphasizing the inhabitants' right to be consulted.

- Importance of Nations (according to Renan):

- Their existence is a good thing, even a necessity.

- They are a guarantee of liberty, which would be lost if the world had only one law and one master.

Frédéric Sorrieu's Utopian Vision (1848)

- French artist Frédéric Sorrieu created a series of four prints depicting his dream of a world composed of 'democratic and social Republics'.

- The first print shows people of Europe and America, from all ages and social classes, marching in a procession and paying homage to the Statue of Liberty.

- The Statue of Liberty is personified as a female figure holding the torch of Enlightenment in one hand and the Charter of the Rights of Man in the other.

- In the foreground, shattered remains of symbols of absolutist institutions lie on the ground.

- Sorrieu's vision depicted peoples grouped as distinct nations, identifiable by their flags and national costumes.

- Leading the procession were the United States and Switzerland, which were already nation-states.

- France followed, identifiable by its revolutionary tricolour flag, having just reached the statue.

- The peoples of Germany followed, bearing a black, red, and gold flag, which, at the time, represented liberal hopes for a unified German nation-state under a democratic constitution.

- Other nations in the procession included Austria, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Lombardy, Poland, England, Ireland, Hungary, and Russia.

- Christ, saints, and angels observed from the heavens, symbolizing fraternity among nations.

- Sorrieu's vision is considered utopian, meaning an ideal society unlikely to exist.

Defining a Nation and Nation-State

- Nationalism emerged in the nineteenth century as a force that brought significant changes in Europe's political and mental landscape.

- The result was the emergence of the nation-state, replacing multi-national dynastic empires.

- A modern state is characterized by a centralized power exercising sovereign control over a defined territory.

- A nation-state is one where the majority of its citizens, not just rulers, develop a sense of common identity and shared history or descent.

- This commonness was not inherent but forged through struggles and the actions of leaders and common people.

Ernst Renan's Understanding of a Nation

- In an 1882 lecture, French philosopher Ernst Renan criticized the idea that a nation is formed by a common language, race, religion, or territory.

- Attributes of a Nation (according to Renan):

- A culmination of a long past of endeavours, sacrifice, and devotion.

- Based on a "social capital" of a heroic past, great men, and glory.

- Essential conditions include common glories in the past, a common will in the present, having performed great deeds together, and the desire to perform still more.

- Defined as a large-scale solidarity.

- Its existence is a "daily plebiscite," meaning a daily affirmation of its inhabitants' will.

- Renan stated that a nation has no real interest in annexing or holding a country against its will, emphasizing the inhabitants' right to be consulted.

- Importance of Nations (according to Renan):

- Their existence is a good thing, even a necessity.

- They are a guarantee of liberty, which would be lost if the world had only one law and one master.

2. The French Revolution and the Idea of the Nation

- First Expression of Nationalism: The French Revolution in 1789 marked the first clear expression of nationalism.

- Shift in Sovereignty: Political and constitutional changes transferred sovereignty from the absolute monarchy to a body of French citizens. The people would now constitute the nation and shape its destiny.

- Measures to Create Collective Identity:

- Ideas of 'la patrie' (the fatherland) and 'le citoyen' (the citizen) emphasized a united community with equal rights under a constitution.

- A new French flag, the tricolour, replaced the former royal standard.

- The Estates General was elected by active citizens and renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths taken, and martyrs commemorated in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system implemented uniform laws.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged, and French (as spoken in Paris) became the common language.

- Mission to Liberate Europe: French revolutionaries declared it their destiny to liberate the peoples of Europe from despotism and help them become nations.

- Spread of Nationalism: News of events in France led to the formation of Jacobin clubs by educated middle classes across Europe. French armies, moving into Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy in the 1790s, carried the idea of nationalism abroad.

- Ideas of 'la patrie' (the fatherland) and 'le citoyen' (the citizen) emphasized a united community with equal rights under a constitution.

- A new French flag, the tricolour, replaced the former royal standard.

- The Estates General was elected by active citizens and renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths taken, and martyrs commemorated in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system implemented uniform laws.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged, and French (as spoken in Paris) became the common language.

3. Napoleon's Impact on Administration and Nationalism

- Administrative Reforms (Napoleonic Code of 1804):

- While Napoleon destroyed democracy by returning to monarchy, he incorporated revolutionary principles to make the administrative system rational and efficient.

- The Civil Code of 1804 (Napoleonic Code) abolished privileges based on birth, established equality before the law, and secured the right to property.

- This code was exported to French-controlled regions like the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, Italy, and Germany.

- He simplified administrative divisions, abolished the feudal system, and freed peasants from serfdom and manorial dues.

- Guild restrictions were removed in towns, and transport and communication systems improved.

- Businessmen and small-scale producers supported uniform laws, standardized weights and measures, and a common national currency for easier movement of goods and capital.

- Mixed Reactions to French Rule:

- Initially, French armies were welcomed as "harbingers of liberty" in places like Holland, Switzerland, Brussels, Mainz, Milan, and Warsaw.

- However, enthusiasm turned to hostility as new administrative arrangements did not equate to political freedom.

- Increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription into French armies outweighed the advantages of administrative changes, leading to discontent. Examples include the depiction of French soldiers as oppressors in Zweibrücken, seizing carts and harassing women.

- While Napoleon destroyed democracy by returning to monarchy, he incorporated revolutionary principles to make the administrative system rational and efficient.

- The Civil Code of 1804 (Napoleonic Code) abolished privileges based on birth, established equality before the law, and secured the right to property.

- This code was exported to French-controlled regions like the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, Italy, and Germany.

- He simplified administrative divisions, abolished the feudal system, and freed peasants from serfdom and manorial dues.

- Guild restrictions were removed in towns, and transport and communication systems improved.

- Businessmen and small-scale producers supported uniform laws, standardized weights and measures, and a common national currency for easier movement of goods and capital.

- Initially, French armies were welcomed as "harbingers of liberty" in places like Holland, Switzerland, Brussels, Mainz, Milan, and Warsaw.

- However, enthusiasm turned to hostility as new administrative arrangements did not equate to political freedom.

- Increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription into French armies outweighed the advantages of administrative changes, leading to discontent. Examples include the depiction of French soldiers as oppressors in Zweibrücken, seizing carts and harassing women.

4. Europe Before Nation-States and Social Structures

-

Fragmented Europe: Mid-eighteenth-century Europe lacked nation-states as we know them today.

- Regions like Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into numerous kingdoms, duchies, and cantons with autonomous rulers.

- Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies, comprising diverse peoples who did not share a collective identity, culture, or often even language.

-

The Habsburg Empire Example:

- This empire over Austria-Hungary was a "patchwork" of many different regions and peoples.

- Included Alpine regions (Tyrol, Austria, Sudetenland) and Bohemia, where aristocracy was German-speaking.

- Included Italian-speaking provinces of Lombardy and Venetia.

- In Hungary, half the population spoke Magyar, the other half various dialects.

- In Galicia, the aristocracy spoke Polish.

- Vast numbers of subject peasant peoples (Bohemians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Roumans) lived within its boundaries.

- The only unifying factor among these diverse groups was a common allegiance to the emperor.

-

Social Classes in Europe:

- Aristocracy: Dominant class, united by a common lifestyle, owned estates and town-houses, spoke French for diplomacy, families connected by marriage. Numerically a small group.

- Peasantry: Majority of the population. In the West, land farmed by tenants and small owners; in Eastern and Central Europe, vast estates cultivated by serfs.

- New Middle Class: Emerged with industrial production and trade, composed of industrialists, businessmen, and professionals. This educated, liberal group popularized ideas of national unity and the abolition of aristocratic privileges.

Fragmented Europe: Mid-eighteenth-century Europe lacked nation-states as we know them today.

- Regions like Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into numerous kingdoms, duchies, and cantons with autonomous rulers.

- Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies, comprising diverse peoples who did not share a collective identity, culture, or often even language.

The Habsburg Empire Example:

- This empire over Austria-Hungary was a "patchwork" of many different regions and peoples.

- Included Alpine regions (Tyrol, Austria, Sudetenland) and Bohemia, where aristocracy was German-speaking.

- Included Italian-speaking provinces of Lombardy and Venetia.

- In Hungary, half the population spoke Magyar, the other half various dialects.

- In Galicia, the aristocracy spoke Polish.

- Vast numbers of subject peasant peoples (Bohemians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Roumans) lived within its boundaries.

- The only unifying factor among these diverse groups was a common allegiance to the emperor.

Social Classes in Europe:

- Aristocracy: Dominant class, united by a common lifestyle, owned estates and town-houses, spoke French for diplomacy, families connected by marriage. Numerically a small group.

- Peasantry: Majority of the population. In the West, land farmed by tenants and small owners; in Eastern and Central Europe, vast estates cultivated by serfs.

- New Middle Class: Emerged with industrial production and trade, composed of industrialists, businessmen, and professionals. This educated, liberal group popularized ideas of national unity and the abolition of aristocratic privileges.

5. Liberal Nationalism and Economic Changes

- Ideology of Liberalism:

- Closely allied with ideas of national unity in early 19th-century Europe.

- Derived from Latin 'liber' (meaning free).

- For the new middle classes, liberalism stood for:

- Freedom for the individual.

- Equality of all before the law.

- Politically: Government by consent, end of autocracy and clerical privileges, a constitution, and representative government through parliament.

- Stressed the inviolability of private property.

- Suffrage (Right to Vote):

- Equality before the law did not mean universal suffrage.

- In revolutionary France, political rights were limited to property-owning men; men without property and all women were excluded.

- Briefly, under the Jacobins, all adult males enjoyed suffrage.

- The Napoleonic Code reverted to limited suffrage and reduced women to the status of minors, subject to the authority of fathers and husbands.

- Women and non-propertied men organized opposition movements demanding equal political rights throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Economic Liberalism:

- Stood for freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital.

- This was a strong demand from the emerging middle classes.

- Example of German-speaking regions: Napoleon created a confederation of 39 states, each with its own currency, weights, and measures. Merchants faced numerous customs barriers (e.g., 11 barriers from Hamburg to Nuremberg, paying 5% duty at each) and time-consuming calculations due to differing units of measurement (e.g., 'elle' for cloth varied significantly by region).

- Zollverein (Customs Union):

- Formed in 1834 at Prussia's initiative, joined by most German states.

- Abolished tariff barriers.

- Reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two.

- Stimulated mobility and economic exchange, harnessing economic interests to national unification.

- Friedrich List, a Professor of Economics, stated that the Zollverein aimed to bind Germans economically into a nation, strengthening it materially and stimulating internal productivity, thereby awakening national sentiment.

- Closely allied with ideas of national unity in early 19th-century Europe.

- Derived from Latin 'liber' (meaning free).

- For the new middle classes, liberalism stood for:

- Freedom for the individual.

- Equality of all before the law.

- Politically: Government by consent, end of autocracy and clerical privileges, a constitution, and representative government through parliament.

- Stressed the inviolability of private property.

- Equality before the law did not mean universal suffrage.

- In revolutionary France, political rights were limited to property-owning men; men without property and all women were excluded.

- Briefly, under the Jacobins, all adult males enjoyed suffrage.

- The Napoleonic Code reverted to limited suffrage and reduced women to the status of minors, subject to the authority of fathers and husbands.

- Women and non-propertied men organized opposition movements demanding equal political rights throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Stood for freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital.

- This was a strong demand from the emerging middle classes.

- Example of German-speaking regions: Napoleon created a confederation of 39 states, each with its own currency, weights, and measures. Merchants faced numerous customs barriers (e.g., 11 barriers from Hamburg to Nuremberg, paying 5% duty at each) and time-consuming calculations due to differing units of measurement (e.g., 'elle' for cloth varied significantly by region).

- Zollverein (Customs Union):

- Formed in 1834 at Prussia's initiative, joined by most German states.

- Abolished tariff barriers.

- Reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two.

- Stimulated mobility and economic exchange, harnessing economic interests to national unification.

- Friedrich List, a Professor of Economics, stated that the Zollverein aimed to bind Germans economically into a nation, strengthening it materially and stimulating internal productivity, thereby awakening national sentiment.

6. Conservatism After 1815

- Conservative Ideals:

- Following Napoleon's defeat in 1815, European governments embraced conservatism.

- Conservatives believed in preserving established, traditional institutions like the monarchy, the Church, social hierarchies, property, and the family.

- Most recognized that modernization (e.g., modern army, efficient bureaucracy, dynamic economy, abolition of feudalism/serfdom) could actually strengthen autocratic monarchies.

- The Congress of Vienna (1815):

- Representatives of Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria met at Vienna, hosted by Austrian Chancellor Duke Metternich.

- Objective: To undo most changes from the Napoleonic Wars.

- Key Outcomes:

- The Bourbon dynasty was restored to power in France, and France lost territories annexed under Napoleon.

- A series of buffer states were set up around France to prevent future expansion (e.g., Kingdom of Netherlands with Belgium to the north, Genoa added to Piedmont in the south).

- Prussia received new territories on its western frontiers, and Austria gained control of northern Italy.

- The German confederation of 39 states (established by Napoleon) was left untouched.

- Russia gained part of Poland, and Prussia gained a portion of Saxony.

- Main intention was to restore overthrown monarchies and create a new conservative order in Europe.

- Autocratic Conservative Regimes:

- Established in 1815, these regimes were autocratic, tolerating no criticism or dissent.

- They imposed censorship laws on newspapers, books, plays, and songs that reflected ideas of liberty and freedom associated with the French Revolution.

- Despite suppression, the memory of the French Revolution continued to inspire liberals, who notably demanded freedom of the press. Caricatures like "The Club of Thinkers" highlighted the suppression of free thought.

- Following Napoleon's defeat in 1815, European governments embraced conservatism.

- Conservatives believed in preserving established, traditional institutions like the monarchy, the Church, social hierarchies, property, and the family.

- Most recognized that modernization (e.g., modern army, efficient bureaucracy, dynamic economy, abolition of feudalism/serfdom) could actually strengthen autocratic monarchies.

- Representatives of Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria met at Vienna, hosted by Austrian Chancellor Duke Metternich.

- Objective: To undo most changes from the Napoleonic Wars.

- Key Outcomes:

- The Bourbon dynasty was restored to power in France, and France lost territories annexed under Napoleon.

- A series of buffer states were set up around France to prevent future expansion (e.g., Kingdom of Netherlands with Belgium to the north, Genoa added to Piedmont in the south).

- Prussia received new territories on its western frontiers, and Austria gained control of northern Italy.

- The German confederation of 39 states (established by Napoleon) was left untouched.

- Russia gained part of Poland, and Prussia gained a portion of Saxony.

- Main intention was to restore overthrown monarchies and create a new conservative order in Europe.

- Established in 1815, these regimes were autocratic, tolerating no criticism or dissent.

- They imposed censorship laws on newspapers, books, plays, and songs that reflected ideas of liberty and freedom associated with the French Revolution.

- Despite suppression, the memory of the French Revolution continued to inspire liberals, who notably demanded freedom of the press. Caricatures like "The Club of Thinkers" highlighted the suppression of free thought.

7. The Revolutionaries and Secret Societies

- Underground Movements: Fear of repression post-1815 drove liberal-nationalists underground.

- Secret societies emerged across Europe to train revolutionaries and spread their ideas.

- Being a revolutionary meant opposing monarchical forms established after the Vienna Congress and fighting for liberty and freedom.

- They viewed the creation of nation-states as a necessary part of this struggle.

- Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872):

- An Italian revolutionary, born in Genoa.

- Member of the secret society Carbonari.

- Exiled in 1831 for attempting a revolution in Liguria.

- Founded two more underground societies:

- Young Italy in Marseilles.

- Young Europe in Berne, with like-minded young men from Poland, France, Italy, and the German states.

- Mazzini believed that God intended nations to be the natural units of mankind.

- He argued that Italy, being a "patchwork of small states and kingdoms," had to be forged into a single unified republic within a wider alliance of nations, as this was the basis of Italian liberty.

- His model inspired secret societies in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Poland.

- His opposition to monarchy and vision of democratic republics frightened conservatives; Metternich called him "the most dangerous enemy of our social order".

- Secret societies emerged across Europe to train revolutionaries and spread their ideas.

- Being a revolutionary meant opposing monarchical forms established after the Vienna Congress and fighting for liberty and freedom.

- They viewed the creation of nation-states as a necessary part of this struggle.

- An Italian revolutionary, born in Genoa.

- Member of the secret society Carbonari.

- Exiled in 1831 for attempting a revolution in Liguria.

- Founded two more underground societies:

- Young Italy in Marseilles.

- Young Europe in Berne, with like-minded young men from Poland, France, Italy, and the German states.

- Mazzini believed that God intended nations to be the natural units of mankind.

- He argued that Italy, being a "patchwork of small states and kingdoms," had to be forged into a single unified republic within a wider alliance of nations, as this was the basis of Italian liberty.

- His model inspired secret societies in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Poland.

- His opposition to monarchy and vision of democratic republics frightened conservatives; Metternich called him "the most dangerous enemy of our social order".

8. The Age of Revolutions: 1830-1848

- Liberal-Nationalist Revolutions: As conservative regimes consolidated power, liberalism and nationalism became increasingly linked to revolutions in regions like the Italian and German states, Ottoman Empire provinces, Ireland, and Poland.

- These were led by educated middle-class elites (professors, school-teachers, clerks, commercial middle classes).

- The July Revolution (France, 1830):

- Overthrew the Bourbon kings, who had been restored after 1815.

- Installed a constitutional monarchy with Louis Philippe as its head.

- Metternich famously remarked, "When France sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold," highlighting its influence.

- Sparked an uprising in Brussels, leading to Belgium breaking away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

- The Greek War of Independence (began 1821):

- Greece had been part of the Ottoman Empire since the 15th century.

- Revolutionary nationalism in Europe fueled a struggle for independence among Greeks.

- Supported by exiled Greeks and West Europeans sympathetic to ancient Greek culture.

- Poets and artists glorified Greece as the "cradle of European civilisation," mobilizing public opinion against the Muslim empire.

- Lord Byron, an English poet, organized funds and fought, dying in 1824.

- The Treaty of Constantinople (1832) recognized Greece as an independent nation.

- The Romantic Imagination and National Feeling:

- Culture played a vital role in creating the idea of the nation, through art, poetry, stories, and music.

- Romanticism: A cultural movement that sought to develop nationalist sentiment, often by criticizing the glorification of reason and science.

- Focused on emotions, intuition, and mystical feelings.

- Aimed to create a sense of a shared collective heritage and a common cultural past as the basis of a nation.

- Johann Gottfried Herder (German philosopher): Claimed true German culture ('das volk') was found among common people and popularized through folk songs, poetry, and dances ('volksgeist').

- The Grimm Brothers:

- Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected old folktales (e.g., Grimms’ Fairy Tales) and published a 33-volume dictionary of the German language.

- They saw French domination as a threat and believed folktales expressed a "pure and authentic German spirit".

- Their projects contributed to opposing French domination and creating a German national identity.

- Importance of Vernacular Language and Folklore:

- Not just to recover an ancient national spirit but also to carry modern nationalist messages to largely illiterate audiences.

- Poland Example: Though partitioned by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, national feelings were kept alive through music and language.

- Karol Kurpinski used operas and music to celebrate the national struggle, turning folk dances like the polonaise and mazurka into nationalist symbols.

- After Russian occupation, Polish was forced out of schools and Russian imposed.

- During an 1831 armed rebellion, the clergy used Polish as a weapon of national resistance for Church gatherings and religious instruction, leading to imprisonment or exile.

- The use of Polish became a symbol of struggle against Russian dominance.

- Hunger, Hardship, and Popular Revolt (1830s-1848):

- The 1830s saw economic hardship due to increased population, job scarcity, overcrowding in cities, and competition from cheap machine-made English goods.

- Peasants in aristocratic regions suffered under feudal dues.

- Food price rises or bad harvests led to widespread poverty.

- The 1848 Revolutions (Paris): Food shortages and unemployment led to protests, Louis Philippe fled, a Republic was proclaimed, and universal male suffrage (for males over 21) and the right to work were granted.

- Silesian Weavers' Revolt (1845): Weavers revolted against contractors who drastically reduced their payments, leading to violence, property destruction, and the shooting of eleven weavers by the army.

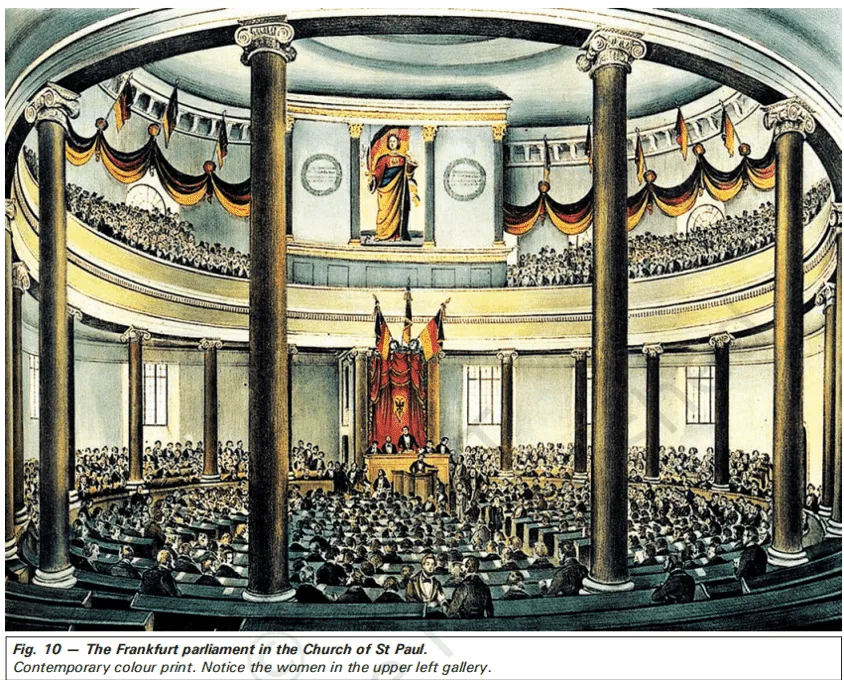

- 1848: The Revolution of the Liberals (Frankfurt Parliament):

- Educated middle classes in places without independent nation-states combined demands for constitutionalism with national unification.

- They sought a nation-state based on parliamentary principles, with a constitution, freedom of the press, and freedom of association.

- German Regions: Political associations of middle-class professionals, businessmen, and artisans met in Frankfurt.

- On May 18, 1848, 831 elected representatives convened the Frankfurt Parliament in the Church of St Paul.

- They drafted a constitution for a German nation to be headed by a monarchy subject to a parliament.

- King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia rejected the crown offered on these terms and joined other monarchs to oppose the assembly.

- The parliament, dominated by the middle classes, alienated workers and artisans by resisting their demands, losing their support. Troops were called in, and the assembly disbanded.

- Women's Rights in the Liberal Movement:

- The issue of political rights for women was controversial.

- Women actively participated, forming political associations, founding newspapers, and taking part in meetings and demonstrations.

- Despite their activism, they were denied suffrage rights in elections and were only admitted as observers in the visitors' gallery during the Frankfurt Parliament.

- Differing Views:

- Carl Welcker (liberal politician): Argued for distinct functions for men (protector, provider, public tasks) and women (home, children, family care), claiming equality would endanger harmony.

- Louise Otto-Peters (feminist activist): Founded a women's journal, stating that "Liberty is indivisible" and free men should not tolerate unfree women.

- Anonymous reader: Criticized the injustice of denying political rights to talented, property-owning women while allowing "stupidest cattle-herder" to vote simply for being a man.

- Concessions from Monarchs: Though conservative forces suppressed liberal movements in 1848, they realized cycles of revolution could only end with concessions.

- Serfdom and bonded labor were abolished in Habsburg dominions and Russia.

- Habsburg rulers granted more autonomy to Hungarians in 1867.

- These were led by educated middle-class elites (professors, school-teachers, clerks, commercial middle classes).

- Overthrew the Bourbon kings, who had been restored after 1815.

- Installed a constitutional monarchy with Louis Philippe as its head.

- Metternich famously remarked, "When France sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold," highlighting its influence.

- Sparked an uprising in Brussels, leading to Belgium breaking away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

- Greece had been part of the Ottoman Empire since the 15th century.

- Revolutionary nationalism in Europe fueled a struggle for independence among Greeks.

- Supported by exiled Greeks and West Europeans sympathetic to ancient Greek culture.

- Poets and artists glorified Greece as the "cradle of European civilisation," mobilizing public opinion against the Muslim empire.

- Lord Byron, an English poet, organized funds and fought, dying in 1824.

- The Treaty of Constantinople (1832) recognized Greece as an independent nation.

- Culture played a vital role in creating the idea of the nation, through art, poetry, stories, and music.

- Romanticism: A cultural movement that sought to develop nationalist sentiment, often by criticizing the glorification of reason and science.

- Focused on emotions, intuition, and mystical feelings.

- Aimed to create a sense of a shared collective heritage and a common cultural past as the basis of a nation.

- Johann Gottfried Herder (German philosopher): Claimed true German culture ('das volk') was found among common people and popularized through folk songs, poetry, and dances ('volksgeist').

- The Grimm Brothers:

- Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected old folktales (e.g., Grimms’ Fairy Tales) and published a 33-volume dictionary of the German language.

- They saw French domination as a threat and believed folktales expressed a "pure and authentic German spirit".

- Their projects contributed to opposing French domination and creating a German national identity.

- Importance of Vernacular Language and Folklore:

- Not just to recover an ancient national spirit but also to carry modern nationalist messages to largely illiterate audiences.

- Poland Example: Though partitioned by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, national feelings were kept alive through music and language.

- Karol Kurpinski used operas and music to celebrate the national struggle, turning folk dances like the polonaise and mazurka into nationalist symbols.

- After Russian occupation, Polish was forced out of schools and Russian imposed.

- During an 1831 armed rebellion, the clergy used Polish as a weapon of national resistance for Church gatherings and religious instruction, leading to imprisonment or exile.

- The use of Polish became a symbol of struggle against Russian dominance.

- The 1830s saw economic hardship due to increased population, job scarcity, overcrowding in cities, and competition from cheap machine-made English goods.

- Peasants in aristocratic regions suffered under feudal dues.

- Food price rises or bad harvests led to widespread poverty.

- The 1848 Revolutions (Paris): Food shortages and unemployment led to protests, Louis Philippe fled, a Republic was proclaimed, and universal male suffrage (for males over 21) and the right to work were granted.

- Silesian Weavers' Revolt (1845): Weavers revolted against contractors who drastically reduced their payments, leading to violence, property destruction, and the shooting of eleven weavers by the army.

- Educated middle classes in places without independent nation-states combined demands for constitutionalism with national unification.

- They sought a nation-state based on parliamentary principles, with a constitution, freedom of the press, and freedom of association.

- German Regions: Political associations of middle-class professionals, businessmen, and artisans met in Frankfurt.

- On May 18, 1848, 831 elected representatives convened the Frankfurt Parliament in the Church of St Paul.

- They drafted a constitution for a German nation to be headed by a monarchy subject to a parliament.

- King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia rejected the crown offered on these terms and joined other monarchs to oppose the assembly.

- The parliament, dominated by the middle classes, alienated workers and artisans by resisting their demands, losing their support. Troops were called in, and the assembly disbanded.

- The issue of political rights for women was controversial.

- Women actively participated, forming political associations, founding newspapers, and taking part in meetings and demonstrations.

- Despite their activism, they were denied suffrage rights in elections and were only admitted as observers in the visitors' gallery during the Frankfurt Parliament.

- Differing Views:

- Carl Welcker (liberal politician): Argued for distinct functions for men (protector, provider, public tasks) and women (home, children, family care), claiming equality would endanger harmony.

- Louise Otto-Peters (feminist activist): Founded a women's journal, stating that "Liberty is indivisible" and free men should not tolerate unfree women.

- Anonymous reader: Criticized the injustice of denying political rights to talented, property-owning women while allowing "stupidest cattle-herder" to vote simply for being a man.

- Serfdom and bonded labor were abolished in Habsburg dominions and Russia.

- Habsburg rulers granted more autonomy to Hungarians in 1867.

9. The Unification of Germany and Italy

- Post-1848 Nationalism: Shifted from liberal-democratic ideals to promoting state power and political domination, often manipulated by conservatives.

- Germany – Unification:

- Middle-class liberals' 1848 attempt at unification was repressed by the monarchy, military, and large landowners (Junkers) of Prussia.

- Prussia took leadership of the national unification movement.

- Otto von Bismarck: Prussia's Chief Minister, was the architect of unification, carried out with the help of the Prussian army and bureaucracy.

- Process of Unification: Three wars over seven years (with Austria, Denmark, and France) ended in Prussian victory.

- Proclamation of German Empire (January 1871): Prussian King William I was proclaimed German Emperor at Versailles.

- The nation-building process showcased the dominance of Prussian state power.

- The new German state emphasized modernizing currency, banking, legal, and judicial systems, with Prussian practices often becoming a model.

- Italy – Unification:

- Italy had a long history of political fragmentation, divided into seven states.

- Only Sardinia-Piedmont was ruled by an Italian princely house.

- Northern Italy was under Austrian Habsburgs, the center by the Pope, and the southern regions by Bourbon kings of Spain.

- The Italian language had many regional variations.

- Giuseppe Mazzini: Had worked on a program for a unitary Italian Republic and formed Young Italy, but revolutionary uprisings in 1831 and 1848 failed.

- Sardinia-Piedmont (under King Victor Emmanuel II) took on the task of unifying Italy through war, aiming for economic development and political dominance.

- Chief Minister Cavour: Led the unification movement. He was neither a revolutionary nor a democrat and spoke French better than Italian.

- Engineered a diplomatic alliance with France, leading to the defeat of Austrian forces in 1859.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi:

- Joined Mazzini's Young Italy movement in 1833 and participated in a republican uprising in Piedmont in 1834, leading to his exile.

- Returned in 1848 and later supported Victor Emmanuel II.

- In 1860, he led the "Expedition of the Thousand" (popularly known as Red Shirts), armed volunteers who marched into South Italy and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

- They gained support from local peasants to drive out Spanish rulers.

- In 1867, Garibaldi led an army to Rome against Papal States (protected by French garrison) but was defeated.

- In 1870, when France withdrew its troops during the war with Prussia, the Papal States finally joined Italy.

- United Italy Proclaimed (1861): Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed king of united Italy.

- Many illiterate peasants in southern Italy, who supported Garibaldi, were unaware of liberal-nationalist ideology and mistakenly believed 'La Talia' (Italia) was Victor Emmanuel's wife.

- The "Strange Case" of Britain:

- Formation of the British nation-state was not a sudden revolution but a long, gradual process.

- Before the 18th century, primary identities were ethnic (English, Welsh, Scot, Irish), each with their own cultural and political traditions.

- The English nation steadily grew in wealth and power, extending its influence.

- The English Parliament, which seized power from the monarchy in 1688, became the instrument for forging a nation-state with England at its center.

- Act of Union (1707): Between England and Scotland, forming the "United Kingdom of Great Britain." This allowed England to impose its influence on Scotland.

- The British Parliament became English-dominated.

- Scottish distinctive culture and political institutions were systematically suppressed; Scottish Highlanders were forbidden to speak Gaelic or wear national dress, and many were forcibly displaced.

- Ireland: Deeply divided between Catholics and Protestants, the English helped Protestants dominate.

- Catholic revolts against British dominance (e.g., Wolfe Tone's failed revolt in 1798) were suppressed.

- Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801.

- A new "British nation" was forged through the propagation of a dominant English culture.

- Symbols of the new Britain (Union Jack, "God Save Our Noble King," English language) were actively promoted, while older nations survived as subordinate partners.

- Middle-class liberals' 1848 attempt at unification was repressed by the monarchy, military, and large landowners (Junkers) of Prussia.

- Prussia took leadership of the national unification movement.

- Otto von Bismarck: Prussia's Chief Minister, was the architect of unification, carried out with the help of the Prussian army and bureaucracy.

- Process of Unification: Three wars over seven years (with Austria, Denmark, and France) ended in Prussian victory.

- Proclamation of German Empire (January 1871): Prussian King William I was proclaimed German Emperor at Versailles.

- The nation-building process showcased the dominance of Prussian state power.

- The new German state emphasized modernizing currency, banking, legal, and judicial systems, with Prussian practices often becoming a model.

- Italy had a long history of political fragmentation, divided into seven states.

- Only Sardinia-Piedmont was ruled by an Italian princely house.

- Northern Italy was under Austrian Habsburgs, the center by the Pope, and the southern regions by Bourbon kings of Spain.

- The Italian language had many regional variations.

- Giuseppe Mazzini: Had worked on a program for a unitary Italian Republic and formed Young Italy, but revolutionary uprisings in 1831 and 1848 failed.

- Sardinia-Piedmont (under King Victor Emmanuel II) took on the task of unifying Italy through war, aiming for economic development and political dominance.

- Chief Minister Cavour: Led the unification movement. He was neither a revolutionary nor a democrat and spoke French better than Italian.

- Engineered a diplomatic alliance with France, leading to the defeat of Austrian forces in 1859.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi:

- Joined Mazzini's Young Italy movement in 1833 and participated in a republican uprising in Piedmont in 1834, leading to his exile.

- Returned in 1848 and later supported Victor Emmanuel II.

- In 1860, he led the "Expedition of the Thousand" (popularly known as Red Shirts), armed volunteers who marched into South Italy and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

- They gained support from local peasants to drive out Spanish rulers.

- In 1867, Garibaldi led an army to Rome against Papal States (protected by French garrison) but was defeated.

- In 1870, when France withdrew its troops during the war with Prussia, the Papal States finally joined Italy.

- United Italy Proclaimed (1861): Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed king of united Italy.

- Many illiterate peasants in southern Italy, who supported Garibaldi, were unaware of liberal-nationalist ideology and mistakenly believed 'La Talia' (Italia) was Victor Emmanuel's wife.

- Formation of the British nation-state was not a sudden revolution but a long, gradual process.

- Before the 18th century, primary identities were ethnic (English, Welsh, Scot, Irish), each with their own cultural and political traditions.

- The English nation steadily grew in wealth and power, extending its influence.

- The English Parliament, which seized power from the monarchy in 1688, became the instrument for forging a nation-state with England at its center.

- Act of Union (1707): Between England and Scotland, forming the "United Kingdom of Great Britain." This allowed England to impose its influence on Scotland.

- The British Parliament became English-dominated.

- Scottish distinctive culture and political institutions were systematically suppressed; Scottish Highlanders were forbidden to speak Gaelic or wear national dress, and many were forcibly displaced.

- Ireland: Deeply divided between Catholics and Protestants, the English helped Protestants dominate.

- Catholic revolts against British dominance (e.g., Wolfe Tone's failed revolt in 1798) were suppressed.

- Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801.

- A new "British nation" was forged through the propagation of a dominant English culture.

- Symbols of the new Britain (Union Jack, "God Save Our Noble King," English language) were actively promoted, while older nations survived as subordinate partners.

10. Visualising the Nation

- Personification of Nations (Allegory):

- Artists in the 18th and 19th centuries personified nations as if they were individuals, typically female figures.

- This female form did not represent a real woman but gave a concrete form to the abstract idea of the nation, becoming an allegory.

- French Allegories: During the French Revolution, artists used female allegories for ideas like Liberty, Justice, and the Republic.

- Liberty's attributes: Red cap, broken chain.

- Justice's attributes: Blindfolded woman carrying weighing scales.

- Marianne: The female allegory for the French nation, a popular Christian name emphasizing a "people's nation".

- Her characteristics were derived from Liberty and the Republic: red cap, tricolour, cockade.

- Statues of Marianne were erected in public squares, and her images marked on coins and stamps, to symbolize national unity and encourage identification.

- German Allegories:

- Germania: The allegory for the German nation.

- Wore a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak symbolized heroism.

- Symbols associated with Germania and their meanings:

- Broken chains: Being freed.

- Breastplate with eagle: Symbol of the German empire – strength.

- Crown of oak leaves: Heroism.

- Sword: Readiness to fight.

- Olive branch around the sword: Willingness to make peace.

- Black, red, and gold tricolour: Flag of the liberal-nationalists in 1848, later banned by German Dukes.

- Rays of the rising sun: Beginning of a new era.

- Artists in the 18th and 19th centuries personified nations as if they were individuals, typically female figures.

- This female form did not represent a real woman but gave a concrete form to the abstract idea of the nation, becoming an allegory.

- Liberty's attributes: Red cap, broken chain.

- Justice's attributes: Blindfolded woman carrying weighing scales.

- Marianne: The female allegory for the French nation, a popular Christian name emphasizing a "people's nation".

- Her characteristics were derived from Liberty and the Republic: red cap, tricolour, cockade.

- Statues of Marianne were erected in public squares, and her images marked on coins and stamps, to symbolize national unity and encourage identification.

- Germania: The allegory for the German nation.

- Wore a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak symbolized heroism.

- Symbols associated with Germania and their meanings:

- Broken chains: Being freed.

- Breastplate with eagle: Symbol of the German empire – strength.

- Crown of oak leaves: Heroism.

- Sword: Readiness to fight.

- Olive branch around the sword: Willingness to make peace.

- Black, red, and gold tricolour: Flag of the liberal-nationalists in 1848, later banned by German Dukes.

- Rays of the rising sun: Beginning of a new era.

11. Nationalism and Imperialism

- Shift in Nationalism (Late 19th Century):

- Nationalism lost its idealistic, liberal-democratic sentiment and became a narrow creed with limited ends.

- Nationalist groups grew intolerant and prone to war.

- Major European powers exploited nationalist aspirations of subject peoples to further their own imperialist goals.

- The Balkans – A Source of Tension:

- The most serious source of nationalist tension in Europe after 1871 was the Balkan region.

- Geography and Ethnicity: Comprised modern-day Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia, Serbia, and Montenegro; inhabitants broadly known as Slavs.

- A large part was under the Ottoman Empire.

- The spread of romantic nationalism combined with the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire made the region explosive.

- Ottoman attempts at modernization and reform largely failed.

- European subject nationalities broke away and declared independence, basing claims on nationality and historical subjugation by foreign powers. They viewed their struggles as attempts to regain lost independence.

- Intense Conflict and Rivalry: Balkan states were fiercely jealous, each seeking to gain more territory at the expense of others.

- The Balkans became a scene of big power rivalry (Russia, Germany, England, Austro-Hungary), all keen on countering other powers' influence and extending their own control.

- This competition led to a series of wars in the region and ultimately the First World War.

- Nationalism's Global Impact:

- Nationalism, when aligned with imperialism, led to disaster in Europe in 1914.

- Meanwhile, colonized countries in the 19th century began to oppose imperial domination.

- Anti-imperial movements were nationalist, struggling to form independent nation-states, inspired by collective national unity forged against imperialism.

- While European ideas of nationalism were not perfectly replicated, the concept of societies organizing into 'nation-states' became widely accepted as natural and universal.

- Nationalism lost its idealistic, liberal-democratic sentiment and became a narrow creed with limited ends.

- Nationalist groups grew intolerant and prone to war.

- Major European powers exploited nationalist aspirations of subject peoples to further their own imperialist goals.

- The most serious source of nationalist tension in Europe after 1871 was the Balkan region.

- Geography and Ethnicity: Comprised modern-day Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia, Serbia, and Montenegro; inhabitants broadly known as Slavs.

- A large part was under the Ottoman Empire.

- The spread of romantic nationalism combined with the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire made the region explosive.

- Ottoman attempts at modernization and reform largely failed.

- European subject nationalities broke away and declared independence, basing claims on nationality and historical subjugation by foreign powers. They viewed their struggles as attempts to regain lost independence.

- Intense Conflict and Rivalry: Balkan states were fiercely jealous, each seeking to gain more territory at the expense of others.

- The Balkans became a scene of big power rivalry (Russia, Germany, England, Austro-Hungary), all keen on countering other powers' influence and extending their own control.

- This competition led to a series of wars in the region and ultimately the First World War.

- Nationalism, when aligned with imperialism, led to disaster in Europe in 1914.

- Meanwhile, colonized countries in the 19th century began to oppose imperial domination.

- Anti-imperial movements were nationalist, struggling to form independent nation-states, inspired by collective national unity forged against imperialism.

- While European ideas of nationalism were not perfectly replicated, the concept of societies organizing into 'nation-states' became widely accepted as natural and universal.

MEANING OF NATIONALISM:

- Apart from this it is also a sense of attachment to a particular culture.

- It should be kept in mind that culture encompasses a variety of factors, like language, cuisine, costumes, folklores, etc.

I. Events and Processes: The Rise of Nationalism in Europe

-

Frédéric Sorrieu's Utopian Vision (1848)

- Frédéric Sorrieu, a French artist, created a series of four prints in 1848, visualising his dream of a world composed of 'democratic and social Republics'.

- The first print (Fig. 1) shows peoples of Europe and America, including men and women of all ages and social classes, marching in a long train.

- They are seen offering homage to the Statue of Liberty as they pass by it.

- Liberty is personified as a female figure holding the torch of Enlightenment in one hand and the Charter of the Rights of Man in the other.

- In the foreground, the shattered remains of symbols of absolutist institutions lie on the earth.

- Sorrieu's utopian vision groups the peoples of the world as distinct nations, identified by their flags and national costumes.

- The United States and Switzerland lead the procession, having already become nation-states by this time.

- France, identified by its revolutionary tricolour, has just reached the statue.

- It is followed by the peoples of Germany, bearing the black, red, and gold flag, which was an expression of liberal hopes in 1848 to unify numerous German-speaking principalities into a nation-state under a democratic constitution.

- Following the German peoples are those of Austria, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Lombardy, Poland, England, Ireland, Hungary, and Russia.

- Christ, saints, and angels gaze from the heavens, used by the artist to symbolize fraternity among the nations of the world.

-

Emergence of the Nation-State

- During the nineteenth century, nationalism emerged as a powerful force that brought about sweeping changes in the political and mental world of Europe.

- The ultimate result of these changes was the emergence of the nation-state, replacing the multi-national dynastic empires of Europe.

- A modern state is defined by a centralized power exercising sovereign control over a clearly defined territory.

- A nation-state is one where the majority of its citizens, not just rulers, developed a sense of common identity and shared history or descent.

- This commonness was not inherent but forged through struggles and the actions of leaders and common people.

Frédéric Sorrieu's Utopian Vision (1848)

- Frédéric Sorrieu, a French artist, created a series of four prints in 1848, visualising his dream of a world composed of 'democratic and social Republics'.

- The first print (Fig. 1) shows peoples of Europe and America, including men and women of all ages and social classes, marching in a long train.

- They are seen offering homage to the Statue of Liberty as they pass by it.

- Liberty is personified as a female figure holding the torch of Enlightenment in one hand and the Charter of the Rights of Man in the other.

- In the foreground, the shattered remains of symbols of absolutist institutions lie on the earth.

- Sorrieu's utopian vision groups the peoples of the world as distinct nations, identified by their flags and national costumes.

- The United States and Switzerland lead the procession, having already become nation-states by this time.

- France, identified by its revolutionary tricolour, has just reached the statue.

- It is followed by the peoples of Germany, bearing the black, red, and gold flag, which was an expression of liberal hopes in 1848 to unify numerous German-speaking principalities into a nation-state under a democratic constitution.

- Following the German peoples are those of Austria, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Lombardy, Poland, England, Ireland, Hungary, and Russia.

- Christ, saints, and angels gaze from the heavens, used by the artist to symbolize fraternity among the nations of the world.

Emergence of the Nation-State

- During the nineteenth century, nationalism emerged as a powerful force that brought about sweeping changes in the political and mental world of Europe.

- The ultimate result of these changes was the emergence of the nation-state, replacing the multi-national dynastic empires of Europe.

- A modern state is defined by a centralized power exercising sovereign control over a clearly defined territory.

- A nation-state is one where the majority of its citizens, not just rulers, developed a sense of common identity and shared history or descent.

- This commonness was not inherent but forged through struggles and the actions of leaders and common people.

II. The French Revolution and the Idea of the Nation

-

Birth of Nationalism in France (1789)

- The French Revolution in 1789 marked the first clear expression of nationalism.

- Prior to this, France was a full-fledged territorial state under an absolute monarch.

- The revolution led to the transfer of sovereignty from the monarchy to a body of French citizens, proclaiming that the people would constitute the nation and shape its destiny.

-

Measures for Collective Identity

- French revolutionaries introduced various measures to create a sense of collective identity among the French people:

- The ideas of la patrie (the fatherland) and le citoyen (the citizen) emphasized a united community with equal rights under a constitution.

- A new French tricolour flag was chosen to replace the former royal standard.

- The Estates General was elected by active citizens and renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths taken, and martyrs commemorated, all in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system was established, formulating uniform laws for all citizens.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged, and French (as spoken in Paris) became the common language of the nation.

- The revolutionaries declared it the mission of the French nation to liberate the peoples of Europe from despotism, helping them become nations.

-

Spread of Nationalism Abroad

- News of events in France led students and educated middle-class members across Europe to set up Jacobin clubs.

- These activities prepared the way for French armies, which moved into Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and much of Italy in the 1790s.

- With the outbreak of revolutionary wars, French armies began to carry the idea of nationalism abroad.

Birth of Nationalism in France (1789)

- The French Revolution in 1789 marked the first clear expression of nationalism.

- Prior to this, France was a full-fledged territorial state under an absolute monarch.

- The revolution led to the transfer of sovereignty from the monarchy to a body of French citizens, proclaiming that the people would constitute the nation and shape its destiny.

Measures for Collective Identity

- French revolutionaries introduced various measures to create a sense of collective identity among the French people:

- The ideas of la patrie (the fatherland) and le citoyen (the citizen) emphasized a united community with equal rights under a constitution.

- A new French tricolour flag was chosen to replace the former royal standard.

- The Estates General was elected by active citizens and renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths taken, and martyrs commemorated, all in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system was established, formulating uniform laws for all citizens.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged, and French (as spoken in Paris) became the common language of the nation.

- The revolutionaries declared it the mission of the French nation to liberate the peoples of Europe from despotism, helping them become nations.

Spread of Nationalism Abroad

- News of events in France led students and educated middle-class members across Europe to set up Jacobin clubs.

- These activities prepared the way for French armies, which moved into Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and much of Italy in the 1790s.

- With the outbreak of revolutionary wars, French armies began to carry the idea of nationalism abroad.

III. Napoleon's Administrative Reforms

-

Incorporating Revolutionary Principles

- Although Napoleon destroyed democracy in France by returning to monarchy, he incorporated revolutionary principles into the administrative field to make the system more rational and efficient.

-

The Civil Code of 1804 (Napoleonic Code)

- Abolished all privileges based on birth.

- Established equality before the law.

- Secured the right to property.

- This Code was exported to regions under French control, including the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, Italy, and Germany.

-

Reforms in Conquered Territories

- Simplified administrative divisions.

- Abolished the feudal system and freed peasants from serfdom and manorial dues.

- Removed guild restrictions in towns.

- Improved transport and communication systems.

- Peasants, artisans, workers, and new businessmen enjoyed new-found freedom.

- Businessmen realized that uniform laws, standardized weights and measures, and a common national currency would facilitate the movement and exchange of goods and capital.

-

Mixed Reactions to French Rule

- Initially, French armies were welcomed as "harbingers of liberty" in many places like Holland, Switzerland, Brussels, Mainz, Milan, and Warsaw.

- However, this initial enthusiasm turned to hostility as it became clear that the new administrative arrangements did not equate to political freedom.

- Factors that outweighed the advantages of administrative changes included increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription into the French armies to conquer the rest of Europe.

Incorporating Revolutionary Principles

- Although Napoleon destroyed democracy in France by returning to monarchy, he incorporated revolutionary principles into the administrative field to make the system more rational and efficient.

The Civil Code of 1804 (Napoleonic Code)

- Abolished all privileges based on birth.

- Established equality before the law.

- Secured the right to property.

- This Code was exported to regions under French control, including the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, Italy, and Germany.

Reforms in Conquered Territories

- Simplified administrative divisions.

- Abolished the feudal system and freed peasants from serfdom and manorial dues.

- Removed guild restrictions in towns.

- Improved transport and communication systems.

- Peasants, artisans, workers, and new businessmen enjoyed new-found freedom.

- Businessmen realized that uniform laws, standardized weights and measures, and a common national currency would facilitate the movement and exchange of goods and capital.

Mixed Reactions to French Rule

- Initially, French armies were welcomed as "harbingers of liberty" in many places like Holland, Switzerland, Brussels, Mainz, Milan, and Warsaw.

- However, this initial enthusiasm turned to hostility as it became clear that the new administrative arrangements did not equate to political freedom.

- Factors that outweighed the advantages of administrative changes included increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription into the French armies to conquer the rest of Europe.

IV. Europe Before Nation-States and the Rise of New Social Classes

-

Fragmented Europe in the Mid-18th Century

- There were no 'nation-states' as we know them today.

- Regions like Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into numerous kingdoms, duchies, and cantons with autonomous rulers.

- Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies, comprising diverse peoples who did not share a collective identity or common culture.

- Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary):

- A "patchwork" of many different regions and peoples.

- Included Alpine regions (Tyrol, Austria, Sudetenland) and Bohemia (predominantly German-speaking aristocracy).

- Comprised Italian-speaking provinces of Lombardy and Venetia.

- In Hungary, half the population spoke Magyar, while the other half spoke various dialects.

- In Galicia, the aristocracy spoke Polish.

- It also housed a mass of subject peasant peoples, including Bohemians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, and Roumans.

- These differences hindered political unity; the only binding tie was common allegiance to the emperor.

-

Social Structure and the New Middle Class

- The Aristocracy:

- Socially and politically the dominant class on the continent, united by a common way of life across regional divisions.

- Owned estates in the countryside and town-houses, spoke French for diplomacy and in high society, and their families were often connected by marriage.

- Numerically, they were a small group.

- The Peasantry:

- Comprised the majority of the population.

- In the west, land was farmed by tenants and small owners; in Eastern and Central Europe, vast estates were cultivated by serfs.

- The New Middle Class:

- Emergence due to the growth of industrial production and trade in Western and Central Europe.

- Industrialization began in England in the late 18th century, and in France and German states during the 19th century.

- Led to the creation of new social groups: a working-class population and middle classes consisting of industrialists, businessmen, and professionals.

- These groups were smaller in number in Central and Eastern Europe until the late 19th century.

- Ideas of national unity, particularly after the abolition of aristocratic privileges, gained popularity among the educated, liberal middle classes.

Fragmented Europe in the Mid-18th Century

- There were no 'nation-states' as we know them today.

- Regions like Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into numerous kingdoms, duchies, and cantons with autonomous rulers.

- Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies, comprising diverse peoples who did not share a collective identity or common culture.

- Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary):

- A "patchwork" of many different regions and peoples.

- Included Alpine regions (Tyrol, Austria, Sudetenland) and Bohemia (predominantly German-speaking aristocracy).

- Comprised Italian-speaking provinces of Lombardy and Venetia.

- In Hungary, half the population spoke Magyar, while the other half spoke various dialects.

- In Galicia, the aristocracy spoke Polish.

- It also housed a mass of subject peasant peoples, including Bohemians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, and Roumans.

- These differences hindered political unity; the only binding tie was common allegiance to the emperor.

Social Structure and the New Middle Class

- The Aristocracy:

- Socially and politically the dominant class on the continent, united by a common way of life across regional divisions.

- Owned estates in the countryside and town-houses, spoke French for diplomacy and in high society, and their families were often connected by marriage.

- Numerically, they were a small group.

- The Peasantry:

- Comprised the majority of the population.

- In the west, land was farmed by tenants and small owners; in Eastern and Central Europe, vast estates were cultivated by serfs.

- The New Middle Class:

- Emergence due to the growth of industrial production and trade in Western and Central Europe.

- Industrialization began in England in the late 18th century, and in France and German states during the 19th century.

- Led to the creation of new social groups: a working-class population and middle classes consisting of industrialists, businessmen, and professionals.

- These groups were smaller in number in Central and Eastern Europe until the late 19th century.

- Ideas of national unity, particularly after the abolition of aristocratic privileges, gained popularity among the educated, liberal middle classes.

V. Liberal Nationalism

-

Core Principles

- Ideas of national unity in early-19th-century Europe were closely allied to the ideology of liberalism.

- The term 'liberalism' derives from the Latin root liber, meaning free.

- For the new middle classes, liberalism stood for freedom for the individual and equality of all before the law.

- Politically, it emphasized the concept of government by consent.

- Since the French Revolution, liberalism advocated for the end of autocracy and clerical privileges, a constitution, and representative government through parliament.

- 19th-century liberals also stressed the inviolability of private property.

-

Limitations on Suffrage

- Equality before the law did not necessarily mean universal suffrage (the right to vote).

- In revolutionary France, the right to vote and be elected was granted exclusively to property-owning men.

- Men without property and all women were excluded from political rights, except for a brief period under the Jacobins when all adult males enjoyed suffrage.

- The Napoleonic Code reverted to limited suffrage and reduced women to the status of a minor, subject to the authority of fathers and husbands.

- Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, women and non-propertied men organized opposition movements demanding equal political rights.

-

Economic Liberalism and the Zollverein

- In the economic sphere, liberalism advocated for the freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital. This was a strong demand from the emerging middle classes.

- Economic Fragmentation Example (German-speaking regions):

- Napoleon's administrative measures created a confederation of 39 states from countless small principalities.

- Each of these states had its own currency, weights, and measures.

- A merchant travelling from Hamburg to Nuremberg in 1833 would face 11 customs barriers, paying about 5% duty at each.

- Duties were based on weight or measurement, and each region had its own system, leading to time-consuming calculations (e.g., the elle for cloth varied significantly by city).

- Creation of the Zollverein:

- These conditions were seen as obstacles to economic exchange and growth by commercial classes, who argued for a unified economic territory.

- In 1834, a customs union or zollverein was formed at Prussia's initiative, joined by most German states.

- The union abolished tariff barriers and reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two.

- A network of railways further stimulated mobility, harnessing economic interests to national unification.

- This wave of economic nationalism strengthened wider nationalist sentiments.

- Friedrich List, a Professor of Economics, stated in 1834 that the zollverein's aim was to bind Germans economically into a nation, strengthening it materially and stimulating internal productivity, thereby awakening national sentiment.

Core Principles

- Ideas of national unity in early-19th-century Europe were closely allied to the ideology of liberalism.

- The term 'liberalism' derives from the Latin root liber, meaning free.

- For the new middle classes, liberalism stood for freedom for the individual and equality of all before the law.

- Politically, it emphasized the concept of government by consent.

- Since the French Revolution, liberalism advocated for the end of autocracy and clerical privileges, a constitution, and representative government through parliament.

- 19th-century liberals also stressed the inviolability of private property.

Limitations on Suffrage

- Equality before the law did not necessarily mean universal suffrage (the right to vote).

- In revolutionary France, the right to vote and be elected was granted exclusively to property-owning men.

- Men without property and all women were excluded from political rights, except for a brief period under the Jacobins when all adult males enjoyed suffrage.

- The Napoleonic Code reverted to limited suffrage and reduced women to the status of a minor, subject to the authority of fathers and husbands.

- Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, women and non-propertied men organized opposition movements demanding equal political rights.

Economic Liberalism and the Zollverein

- In the economic sphere, liberalism advocated for the freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital. This was a strong demand from the emerging middle classes.

- Economic Fragmentation Example (German-speaking regions):

- Napoleon's administrative measures created a confederation of 39 states from countless small principalities.

- Each of these states had its own currency, weights, and measures.

- A merchant travelling from Hamburg to Nuremberg in 1833 would face 11 customs barriers, paying about 5% duty at each.

- Duties were based on weight or measurement, and each region had its own system, leading to time-consuming calculations (e.g., the elle for cloth varied significantly by city).

- Creation of the Zollverein:

- These conditions were seen as obstacles to economic exchange and growth by commercial classes, who argued for a unified economic territory.

- In 1834, a customs union or zollverein was formed at Prussia's initiative, joined by most German states.

- The union abolished tariff barriers and reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two.

- A network of railways further stimulated mobility, harnessing economic interests to national unification.

- This wave of economic nationalism strengthened wider nationalist sentiments.

- Friedrich List, a Professor of Economics, stated in 1834 that the zollverein's aim was to bind Germans economically into a nation, strengthening it materially and stimulating internal productivity, thereby awakening national sentiment.

VI. A New Conservatism after 1815

-

Conservative Ideology

- Following Napoleon's defeat in 1815, European governments were driven by a spirit of conservatism.

- Conservatives believed that established, traditional institutions of state and society – such as the monarchy, the Church, social hierarchies, property, and the family – should be preserved.

- Most conservatives, however, did not propose a return to pre-revolutionary society; they realized that modernization could strengthen traditional institutions like the monarchy.

- A modern army, efficient bureaucracy, dynamic economy, and the abolition of feudalism and serfdom could make state power more effective and autocratic monarchies stronger.

-

The Congress of Vienna (1815)

- Representatives of the European powers (Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria) who had collectively defeated Napoleon met at Vienna.

- The Congress was hosted by the Austrian Chancellor Duke Metternich.

- The delegates drew up the Treaty of Vienna of 1815 with the objective of undoing most of the changes brought about during the Napoleonic wars.

- Key Outcomes:

- The Bourbon dynasty was restored to power in France, and France lost territories annexed under Napoleon.